The Topline

- Alberta’s provincial government has ordered high schools to remove books with “explicit sexual visuals” from libraries.

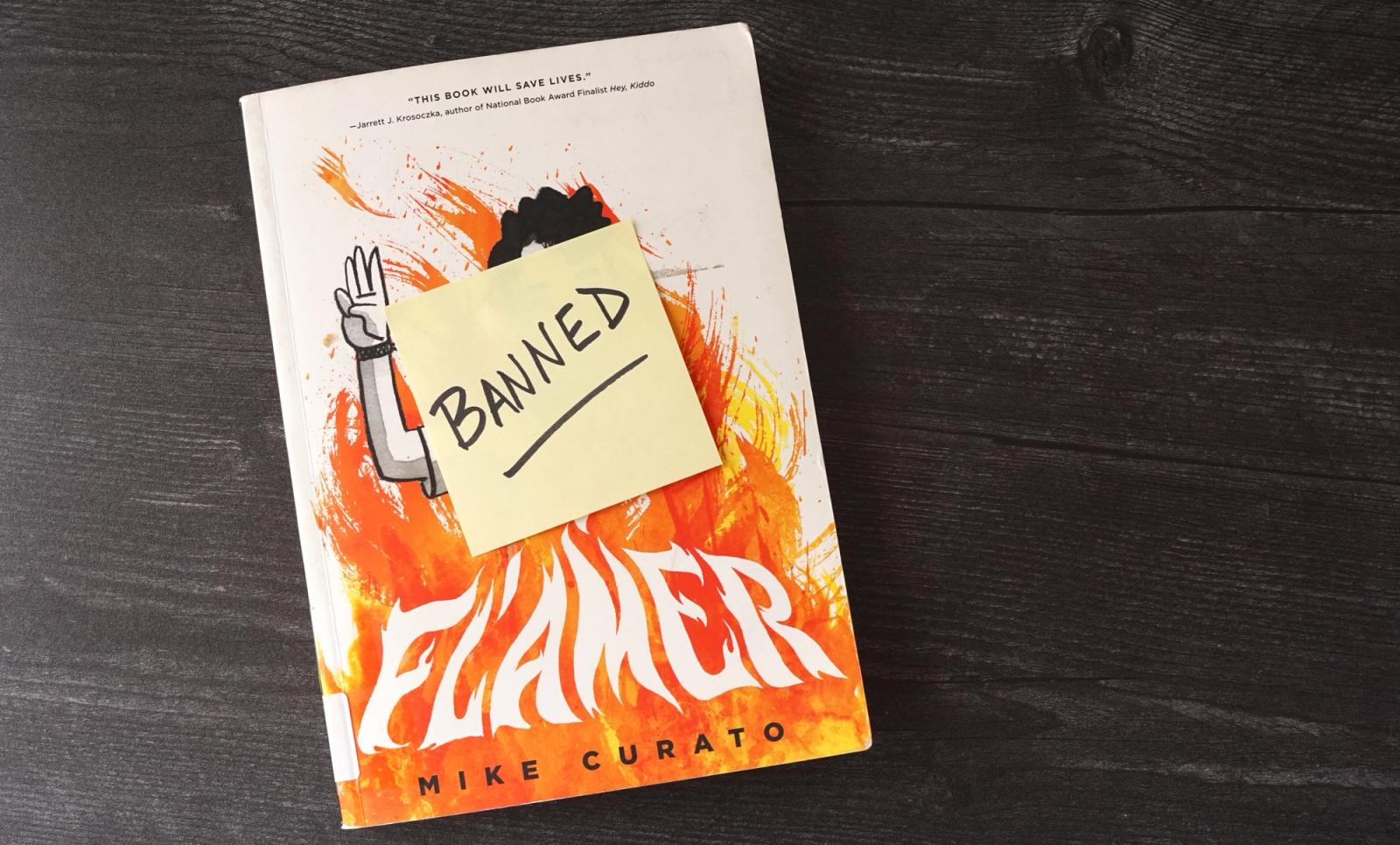

- Four graphic novels in particular were targeted – Gender Queer, Fun Home, Blankets, and Flamer, three of which depict sexual encounters involving LGBTQ+ characters

- Provincial school boards had initially flagged over 200 titles — including George Orwell’s 1984 and Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale — but the backlash forced the province to pause the directive and scale back the titles it would ban

Switch sides,

back and forth

“High schooler” doesn’t mean “adult”

Age of consent laws don’t magically evaporate when “graphic novel” is applied to the label of books containing sexual imagery. In any other context, showing minors graphic illustrations of oral sex, masturbation, or strap-on use could land you in serious legal trouble. Why would a school library be an exception?

Fun Home and Gender Queer may be award-winning, but that doesn’t make them developmentally appropriate for high schoolers. Parents groups, including Action4Canada and Parents for Choice in Education, have lobbied against these books specifically, not necessarily because they hate art (though they might, who knows), but because schools aren’t neutral distribution points for such content. Schools don’t allow the Kama Sutra on library shelves, after all.

Education Minister Demetrios Nicolaides has argued that the prose in books is filtered through literacy, and maturity is required to understand the contents of those words. Pictures, on the other hand, are instant. A 15-year-old might skim past the nuance in Handmaid’s Tale, but no one misses a panel of oral sex.

It’s not about queerness or prudishness — it’s about the medium. From this perspective, banning a handful of graphic novels isn’t censorship. It’s just applying the same standards to comic books as to Playboy.

So what?

This is ultimately about culture war politics. These books are rallying cries for certain parents’ rights activists groups. By banning the four titles at the centre of the maelstrom, along with other books containing similar imagery (including graphic heterosexual illustrations and pictures) Smith can tell her base she’s protecting kids without tossing To Kill a Mockingbird into the bonfire. Cynical? Hell yeah. Effective? Well…

It solves absolutely nothing

When you ban images of sexuality in educational contexts, you don’t eliminate exposure, you just outsource it to the internet. By stripping libraries of visual depictions of sexuality, the government isn’t “protecting innocence.” It’s engineering ignorance.

For many teens, especially queer ones, these books double as informal sex ed. They provide context, consent, and reassurance that their experiences aren’t shameful or unique. Research consistently shows that comprehensive sex ed gives young people the knowledge and language to understand consent, which reduces their vulnerability to abuse.

And there is an education component to these books, whether we’re comfortable with that idea or not.

School libraries already contain novels with rape, incest, domestic violence, and explicit sexual descriptions, all in text. The Bible, rife with violence – sexual and otherwise – is permitted in Alberta school libraries. If we accept that students can process those words with maturity, why is a drawing or a picture suddenly too hot to handle? It isn’t.

It’s important to note that all graphic visual depictions of sex are now banned in Alberta public schools, it’s not just these LGBTQ+ coming-of-age memoirs. But these were the four books at the centre of the debate, and the groups calling for their removal have expressed anti-LGBTQ+ rhetoric leading up to Smith’s government pulling the titles.

This decision sends an uncomfortable message to queer teens: your identity is too explicit for school shelves. It’s stigmatization, full stop.

So what?

Smith’s government tried to blunt the backlash by narrowing the ban to visuals only, but a ban is still a ban. Students who might see themselves reflected in these books are being told those reflections are inappropriate. Today, it’s sexual imagery (oh the horror!). Tomorrow it’s anything a lobby group finds uncomfortable.

Are graphic depictions of sex in sex ed next? By Smith’s logic, it should be. We’re shielding teenagers not just from thoughtful literature with deep impact, but from a basic understanding of what their sexuality is, as well – at a pivotal time in their development.